.jpg) Photo courtesy of Robin Hoecker

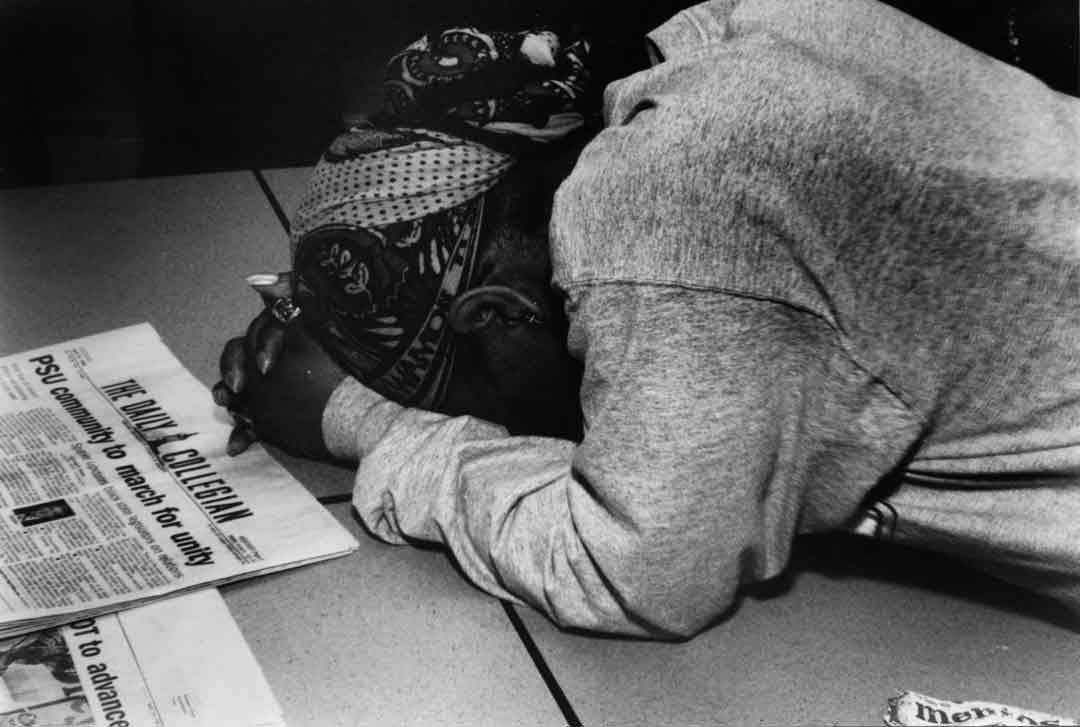

Photo courtesy of Robin HoeckerI took my first photojournalism class as a junior at Penn State. While there, I completed a yearlong documentary project about black student protests on campus. Twenty years later, despite two graduate degrees and years working as a photojournalist, I know that those photographs I took in college remain the most important work I've ever done.

The project began as a class assignment. I documented a silent march around Beaver Stadium after black student leaders, football players and a university trustee received threatening letters in the mail. For the next year, I continued to document these students' efforts to get the university to be more responsive to racial issues.

Photo courtesy of Robin Hoecker

Photo courtesy of Robin Hoecker

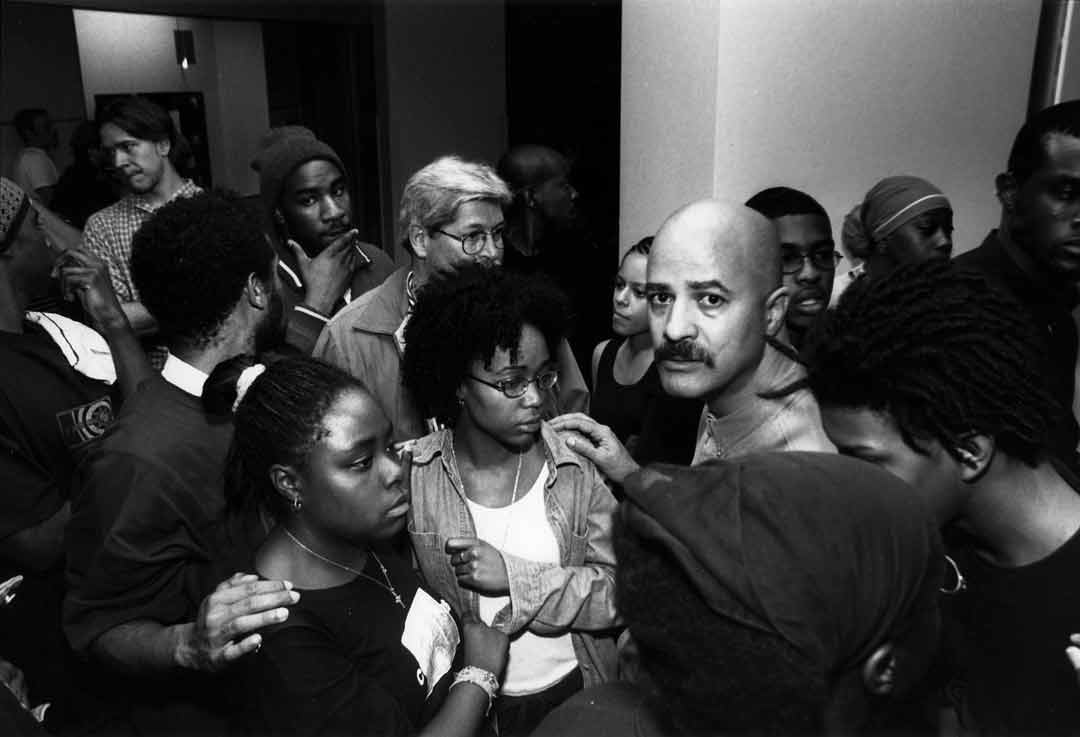

They spoke at faculty senate meetings and held hearings with state legislators. The students wanted the university to take such threats and the fear they caused seriously. They also wanted the university to invest more in research and teaching about racism and for there to be more accountability when the university failed to meet its diversity goals. Their movement reached a peak after students interrupted a nationally televised football game and occupied the student union building for 10 days, actions that received national attention.

My images are flawed and grainy. It was 2000, before digital cameras came on the scene, so I was still processing and printing my film in a darkroom, with mixed results. There was a long delay from when I snapped the shutter to when I would see the faces slowly appear in a tray of chemicals. Those faces showed frustration, fear, anger and sadness, but also determination, resolve and joy. I spent a lot of time looking at those faces and trying to understand what was happening and why.

As extraordinary as the protests were, they were not unique. Major protests occurred at Penn State in 1969, 1988 and 2000, and to some extent in 2014 with the Black Lives Matter movement. What happened at Penn State was happening nationwide as students reacted to racial inequities on campus. That, combined with current events and political tensions, made for a powerful and combustible mix. The progress and agreements made in one era would erode, and then the next group, under the right circumstances, would raise the same demands years later. In other words, major protests break out about once a generation.

Photo courtesy of Robin Hoecker

Photo courtesy of Robin Hoecker

My current research examines this repetitive cycle, using Penn State as an in-depth case study. I am working with librarians and filing Freedom of Information Act requests to learn more about how administrators approached negotiations with students in different eras. I hope to interview leaders of the protests from different generations. I am also working to make sure that the documents I come across are available for other researchers through Project STAND (Student Activism Now Documented), a collaboration of archivists trying to document the activism of marginalized groups.

I am still fascinated by what I witnessed. I recognize how important my visual documents are to understanding the history of Penn State, the role of black student protests at universities and the complicated process of social change.

As George Orwell wrote in the book "1984," "Who controls the past controls the future; who controls the present controls the past." My goal with this project is to make sure this part of history is documented and given the attention it deserves.

Robin Hoecker is an assistant professor of

journalism.

Originally published in

Conversations (Spring 2020).