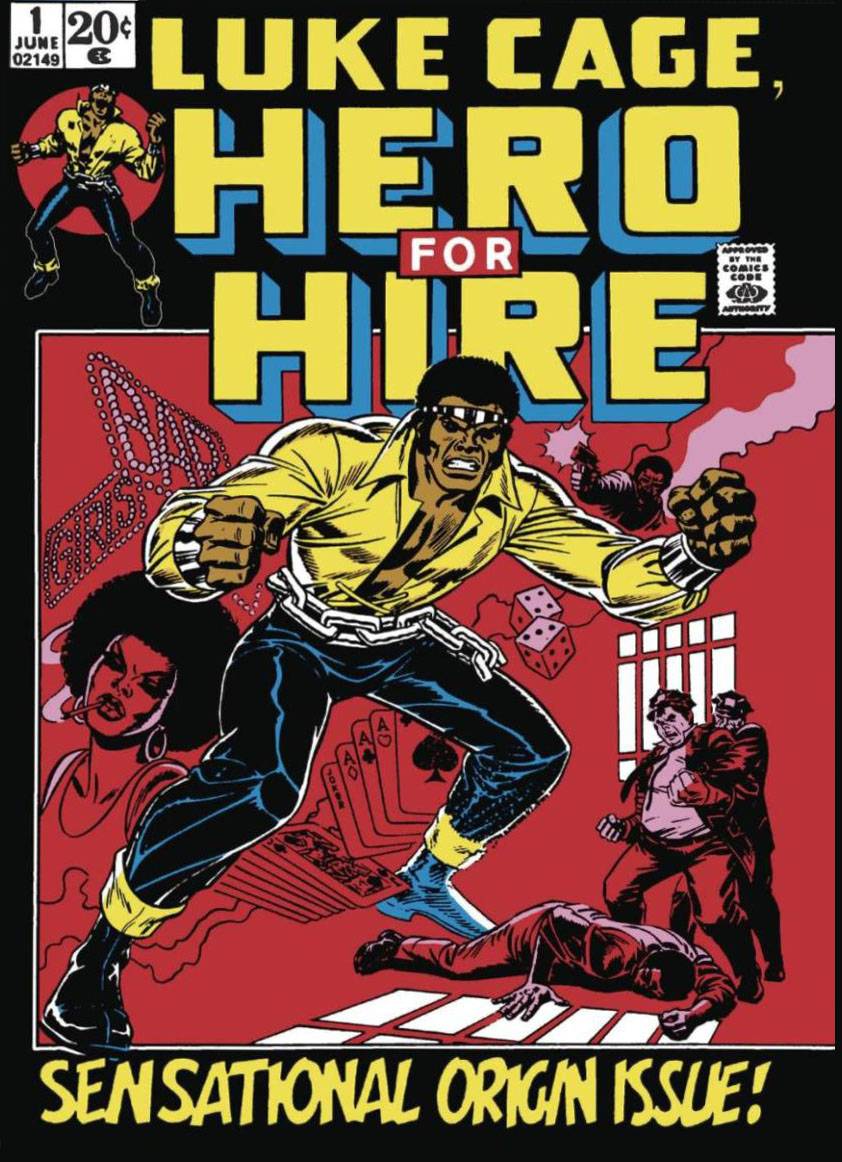

Superman’s iconic red cape hints to us that he can fly. Batman’s mask explains his alter-ego, and Spider-Man’s web-emblazoned jumpsuit communicates his arachnid-like tendencies. But Luke Cage’s original costume—silver headband and bracelets, an open yellow shirt tucked into the top of his chain-link belt—t

ells us little about his character and more about perceptions of black culture in 1972, when the first Luke Cage comic book was released.

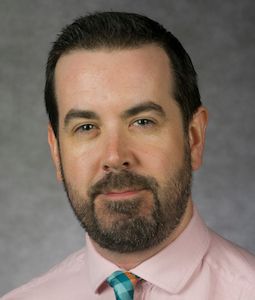

In his essay, “Bare Chests, Silver Tiaras and Removable Afros: The Visual Design of Black Comic Book Superheroes,” Blair Davis, assistant professor of Media and Cinema Studies, explores the evolution of black superhero costumes and what each iteration communicates about the era in which it was created. Recently published as a chapter in The Blacker the Ink: Constructions of Black Identity in Comics and Sequential Art, Davis discusses his essay, his research and his findings below.

How did you become involved with “The Blacker the Ink?” Why were you interested in the project?

I felt that more research needed to be done on comic books and black identity. I’ve taught courses on African American cinema and popular culture, and I’ve researched comic books, so the book project seemed like a natural extension of both. I have spent many decades reading comics and wondering why there weren’t more black characters. I have also heard that the costumes of black superheroes are often laughed at by both white and black fans—like Luke Cage’s silver tiara and Black Lightning’s removable afro wig. Writing this essay was a way to explore the reasons behind those choices.

In your essay, you say that each black superhero’s costume is rife with hints of white perceptions of black culture at the time. What led you to this conclusion? What are some examples?

One way the visual design of the characters I examined differs from white superheroes is that they all have varying degrees of exposed flesh, such as Luke Cage’s and Black Lightning’s bare chests, Vixen’s backless costume, Storm’s bare thighs and shoulders, and Cyborg’s bare chest, shoulders and thighs. There is a pattern here of putting black bodies on display in a way that emphasizes masculinity/femininity and sexuality that is not seen among most white superheroes. In my essay, I conclude that black superheroes serve as touchstones for how white America regards black identity in any given period.

When were the first black superheroes introduced? Was this a reflection of the time as well?

The first modern black superhero was Marvel’s Black Panther in the late 1960s. A movie based on the character is actually set to be released in 2018. I think that Marvel was reacting to social changes and the civil rights movement in the 1960s by introducing a black superhero, and attempting to provide some diversity in the pages of titles like The Avengers.

Have you used any of the research you did for the essay in your classes at DePaul?

I have referred to it when I teach African American cinema as an example of what was going on in other media in the 1970s with regards to representations of black identity, especially how masculinity is portrayed. I also teach courses in comics studies, so this essay has helped me to better confront issues of race, gender and class in comics.

Faculty Bio

Professor Blair Davis

Professor Blair Davis received his PhD from the department of Communication Studies at McGill University in 2007, and received his MA in Communication and BA in English from Simon Fraser University.

Davis previously taught film and media studies at both Simon Fraser University and the University of New Brunswick before joining DePaul. His specific teaching and research interests include classical Hollywood cinema, B-movies, economic contexts of cinema, the intersections of film and television with other media industries, film genre studies (especially horror, film noir and science-fiction), comic books, media ecology, African American cinema, and hip-hop culture.